So, following

Thoughts About Time-Binding 1 and

Thoughts About Time-Binding 2, it's time for the third installment of this timely series.

But first, a big THANK YOU to Bruce Kodish for posting an entry on his own blog saying nice things about what I've been writing here:

Some Strate Talk About Time-Binding. Bruce is our leading expert on Alfred Korzybski who, as you know, is the fellow who came up with the idea of time-binding, and general semantics, and was the founder of the

Institute of General Semantics. Bruce is currently completing a biography of Korzbyski, and his blog,

Korzybski Files, is a great resource available to all (and I have added a link to this blog to my listing over on the right).

Now then, back to the binding of Isaac, er, I mean the binding of time (sorry, some residue from the High Holy Days). Korzbyski's concept of time-binding is related to the idea that human beings have supplemented biological evolution with cultural evolution, and through culture, language and symbolic communication, the accumulation of knowledge, and technological innovation, we have progress. Time-binding is a basic characteristic of the human species as a "class of life," to use Korzybski's own terms, so that it is, in one sense, universal to all human societies.

But in another sense, Korzybski was non-Aristotelian even before coming up with his non-Aristotelian system, and realized that time-binding of one sort is not the same as time-binding of another sort. Specifically, some forms of time-binding allow for relatively rapid progress, while others allow for only slow, gradual evolution. The difference was akin, in metaphoric-mathematical terms (mathemetaphor?, hey Ray Gozzi, how about that?), to the difference between arithmetic and geometric progressions.

So, all human societies are characterized by slow, gradual time-binding. Some human societies, however, managed to develop an accelerated form of time-binding in specialized sectors, specifically those associated with science, mathematics, engineering, and technology. And so, Korzybski reasoned, if we could generalize from those sectors to the rest of society, we could achieve rapid progress in all aspects of human life, allowing our species to reach its true potential, which he referred to in the title of his book as the

Manhood of Humanity.

Having not yet arrived at the discipline of general semantics, Korzybski instead puts forth a vaguer notion involving the application of scientific method to all human affairs, and refers to it as

human engineering. This was an unfortunate choice of words, as it at once summons associations with Communist attempts to create a "new man" via Pavlovian conditioning techniques, Nazi eugenics and racial sanitation/ethnic cleansing, controversial notions of social engineering, and in contemporary culture, genetic engineering. And not surprisingly, Korzybski backed away from this sort of terminology later on.

Engineering had a cachet in the early 20th century that it lost in light of the Nazi's all-too-efficient concentration camps and gas chambers, and the atomic bomb. And after all, what we're really talking about here is

education. A much better term, don't you think?

But let's look at some of what Korzybski said in

Manhood of Humanity, shall we? For example, here he draws a sharp contrast between science and non-science (or should that be nonsense?):

Some technological invention is made, like that of a steam engine or a printing press, for example; or some discovery of scientific method, like that of analytical geometry or the infinitesimal calculus; or some discovery of natural law, like that of falling bodies or the Newtonian law of gravitation. What happens? What is the effect upon the progress of knowledge and invention? The effect is stimulation. Each invention leads to new inventions and each discovery to new discoveries; invention breeds invention, science begets science, the children of knowledge produce their kind in larger and larger families; the process goes on from decade to decade, from generation to generation, and the spectacle we behold is that of advancement in scientific knowledge and technological power according to the law and rate of a rapidly increasing geometric progression or logarithmic function.

And now what must we say of the so-called sciences—the pseudo sciences—of ethics and jurisprudence and economics and politics and government? For the answer we have only to open our eyes and behold the world. By virtue of the advancement that has long been going on with ever accelerated logarithmic rapidity in invention, in mathematics, in physics, in chemistry, in biology, in astronomy and in applications of them, time and space and matter have been already conquered to such an extent that our globe, once so seemingly vast, has virtually shrunken to the dimensions of an ancient province; and manifold peoples of divers tongues and traditions and customs and institutions are now constrained to live together as in a single community. There is thus demanded a new ethical wisdom, a new legal wisdom, a new economical wisdom, a new political wisdom, a new wisdom in the affairs of government. For the new visions our anguished times cry aloud but the only answers are reverberated echoes of the wailing cry mingled with the chattering voices of excited public men who know not what to do. Why? What is the explanation? The question is double: Why the disease? And why no remedy at hand? The answer is the same for both. And the answer is that the so-called sciences of ethics and jurisprudence and economics and politics and government have not kept pace with the rapid progress made in the other great affairs of man; they have lagged behind; it is because of their lagging that the world has come to be in so great distress; and it is because of their lagging that they have not now the needed wisdom to effect a cure.

Do you ask why it is that the “social” sciences—the so-called sciences of ethics, etc.—have lagged behind? The answer is not far to seek nor difficult to understand. They have lagged behind, partly because they have been hampered by the traditions and the habits of a bygone world—they have looked backward instead of forward; they have lagged behind, partly because they have depended upon the barren methods of verbalistic philosophy—they have been metaphysical instead of scientific; they have lagged behind, partly because they have been often dominated by the lusts of cunning “politicians” instead of being led by the wisdom of enlightened statesmen; they have lagged behind, partly because they have been predominantly concerned to protect “vested interests,” upon which they have in the main depended for support; the fundamental cause, however, of their lagging behind is found in the astonishing fact that, despite their being by their very nature most immediately concerned with the affairs of mankind, they have not discovered what Man really is but have from time immemorial falsely regarded human beings either as animals or else as combinations of animals and something supernatural. With these two monstrous conceptions of the essential nature of man I shall deal at a later stage of this writing.

At present I am chiefly concerned to drive home the fact that it is the great disparity between the rapid progress of the natural and technological sciences on the one hand and the slow progress of the metaphysical, so-called social “sciences” on the other hand, that sooner or later so disturbs the equilibrium of human affairs as to result periodically in those social cataclysms which we call insurrections, revolutions and wars. The reader should note carefully that such cataclysmic changes—such “jumps,” as we may call them—such violent readjustments in human affairs and human relationships—are recorded throughout the history of mankind. And I would have him see clearly that, because the disparity which produces them increases as we pass from generation to generation—from term to term of our progressions—the “jumps” in question occur not only with increasing violence but with increasing frequency. (pp. 19-23)

Looking at what Korzybski is saying from a media ecological perspective, we see an emphasis on the role of technology and science in human history, what Siegfried Gideon referred to as

anonymous history. We also see a critique of the

scientism of the social sciences. Moreover, we can discern in the disparity the need to find a way to gain some measure of control over our technological and scientific development.

Further, in considering what it means to be human, which was one of the basic questions Korzybski was asking (as discussed in

Thoughts About Time-Binding 2), he argues that human beings are by nature social and cooperative--Kenneth Burke makes a similar argument in

Rhetoric of Motives, stating that the whole point of symbolic communication is to establish, maintain, and increase a sense of common ground and identification among individuals), and that we are by nature creators (a point made more recently by Daniel Boorstin, in

The Creators, natch) and inventors, that we require technology to survive (a common point in much of the anthropological literature, and especially among technology scholars in the media ecology intellectual tradition, going back at least to Lewis Mumford):

What is achieved in blaming a man for being selfish and greedy if he acts under the influence of a social environment and education which teach him that he is an animal and that selfishness and greediness are of the essence of his nature?

Even so eminent a philosopher and psychologist as Spencer tells us: “Of self-evident truths so dealt with, the one which here concerns us is that a creature must live before it can act. ... Ethics has to recognize the truth that egoism comes before altruism.” This is true for ANIMALS, because animals die out from lack of food when their natural supply of it is insufficient because they have NOT THE CAPACITY TO PRODUCE ARTIFICIALLY. But it is not true for the HUMAN DIMENSION.

Why not? Because humans through their time-binding capacity are first of all creators and so their number is not controlled by the supply of unaided nature, but only by men's artificial productivity, which is THE MATERIALIZATION OF THEIR TIME-BINDING CAPACITY.

Man, therefore, by the very intrinsic character of his being, MUST ACT FIRST, IN ORDER TO BE ABLE TO LIVE (through the action of parents—or society) which is not the case with animals. The misunderstanding [pg 073] of this simple truth is largely accountable for the evil of our ethical and economic systems or lack of systems. As a matter of fact, if humanity were to live in complete accord with the animal conception of man, artificial production—time-binding production—would cease and ninety per cent of mankind would perish by starvation. It is just because human beings are not animals but are time-binders—not mere finders but creators of food and shelter—that they are able to live in such vast numbers.

Here even the blind must see the effect of higher dimensionality, and this effect becomes in turn the cause of other effects which produce still others, and so on in an endless chain. WE LIVE BECAUSE WE PRODUCE, BECAUSE WE ARE ACTING IN TIME AND ARE NOT MERELY ACTING IN SPACE—BECAUSE MAN IS NOT A KIND OF ANIMAL. It is all so simple, if only we apply a little sound logic in our thinking about human nature and human affairs. If human ethics are to be human, are to be in the human dimension, the postulates of ethics must be changed; FOR HUMANITY IN ORDER TO LIVE MUST ACT FIRST; the laws of ethics—the laws of right living—are natural laws—laws of human nature—laws having their whole source and sanction in the time-binding capacity and time-binding activity peculiar to man. Human excellence is excellence in time-binding, and must be measured and rewarded by time-binding standards of worth.

Humanity, in order to live, must produce creatively and therefore must be guided by applied science, by technology; and this means that the so-called social sciences of ethics, jurisprudence, psychology, economics, sociology, politics, and government must be emancipated from medieval metaphysics; they must be made scientific; they must be technologized; they must be made to progress and to function in the proper dimension—the human dimension and not that of animals: they must be made time-binding sciences.

Can this be done? I have no doubt that it can. For what is human life after all?

To a general in the battlefield, human life is a factor which, if properly used, can destroy the enemy. To an engineer human life is an equivalent to energy, or a capacity to do work, mental or muscular, and the moment something is found to be a source of energy and to have the capacity of doing work, the first thing to do, from the engineer's point of view, is to analyse the generator with a view to discovering how best to conserve it, to improve it, and bring it to the level of maximum productivity. Human beings are very complicated energy-producing batteries differing widely in quality and magnitude of productive power. Experience has shown that these batteries are, first of all, chemical batteries producing a mysterious energy. If these batteries are not supplied periodically with a more or less constant quantity of some chemical elements called food and air, the batteries will cease to function—they will die. In the examination of the structure of these batteries we find that the chemical base is very much accentuated all through the structure. This chemical generator is divided into branches each of which has a very different rôle which it must perform in harmony with all the others. The mechanical parts of the structure are built in conformity to the rules of mechanics and are automatically furnished with lubrication and with chemical supplies for automatically renewing worn-out parts. The chemical processes not only deposit particles of mass for the structure of the generator but produce some very powerful unknown kinds of energies or vibrations which make all the chemical parts function; we find also a mysterious apparatus with a complex of wires which we call brain glands, and nerves; and, finally, these human batteries have the remarkable capacity of reproduction.

These functions are familiar to everybody. From the knowledge of other physical, mechanical and chemical phenomena of nature, we must come to the conclusion, that this human battery is the most perfect example of a complex engine; it has all the peculiarities of a chemical battery combined with a generator of a peculiar energy called life; above all, it has mental or spiritual capacities; it is thus equipped with both mental and mechanical means for producing work. The parts and functions of this marvelous engine have been the subject of a vast amount of research in various special branches of science. A very noteworthy fact is that both the physical work and the mental work of this human engine are always accompanied by both physical and chemical changes in the structure of its machinery—corresponding to the wear and tear of non-living engines. It also presents certain sexual and spiritual phenomena that have a striking likeness to certain phenomena, especially wireless phenomena, to electricity and to radium. This human engine-battery is of unusual strength, durability and perfection; and yet it is very liable to damage and even wreckage, if not properly used. The controlling factors are very delicate and so the engine is very capricious. Very special training and understanding are necessary for its control.

The reader may wish to ask: What is the essence of the time-binding power of Man? Talk of essences is metaphysical—it is not scientific. Let me explain by an example.

What is electricity? The scientific answer is: electricity is that which exhibits such and such phenomena. Electricity means nothing but a certain group of phenomena called electric. We are studying electricity when we are studying those phenomena. Thus it is in physics—there is no talk of essences. So, too, in Human Engineering—we shall not talk of the essence of time-binding but only of the phenomena and the laws thereof. What has led to the development of electric appliances is knowledge of electrical phenomena—not metaphysical talk about the electrical essence. And what will lead to the science and art of Human Engineering is knowledge of time-binding phenomena—not vain babble about an essence of time-binding power. There is no mystery about the word time-binding. Some descriptive term was necessary to indicate that human capacity which discriminates human beings from animals and marks man as man. For that use—the appropriateness of the term time-binding becomes more and more manifest upon reflection. (pp. 72-77)

Note that all instances of capitalization and italics are from the original text.

Interesting to see the reference to the materialization of time-binding, in reference to human invention, innovation, and technology. This was an important point that unfortunately becomes overshadowed by the emphasis on scientific method and human engineering in

Manhood of Humanity, and verbal/symbolic communication in Korzybski's later work on general semantics, but of course it was enough for him to deal with those topics. The comparison of the human being to a battery may put you in mind of the science fiction film,

The Matrix, in which human beings actually were depicted as living batteries kept in a virtual coma by artificially intelligent machines. There is also a reversal here from the way that scholars of technology understand technology to be extensions of the biological and human, a kind of reverse engineering if you will. But there is also an understanding that the material technology (or biology) cannot be considered separately from the software, instructions, technique, operating system. The reference is not to the metaphysical, but the methodological, and metacommunicational, or put another way, the medium.

Here now is a kind of summary statement from Korzybski:

It is essential to keep in mind the nature of our enterprise as a whole, which is that of pointing the way to the science and art of Human Engineering and laying the foundations thereof; we have seen Human Engineering, when developed, is to be the science and art of so directing human energies and capacities as to make them contribute most effectively to the advancement of human welfare; we have seen that this science and art must have its basis in a true conception of human nature—a just conception of what Man really is and of his natural place in the complex of the world; we have seen that the ages-old and still current conceptions of man—zoological and mythological conceptions, according to which human beings are either animals or else hybrids of animals and gods—are mainly responsible for the dismal things in human history; we have seen that man, far from being an animal or a compound of natural and supernatural, is a perfectly natural being characterized by a certain capacity or power—the capacity or power to bind time; we have seen that humanity is, therefore, to be rightly conceived and scientifically defined as the time-binding class of life; we have seen that, therefore, the laws of time-binding energies and time-binding phenomena are the laws of human nature; we have seen that this conception of man—which must be the basic concept, the fundamental principle and the perpetual guide and regulator of Human Engineering—is bound to work a profound transformation in all our views on human affairs and, in particular, must radically alter the so-called social “sciences”—the life-regulating “sciences” of ethics, sociology, economics, politics and government—advancing them from their present estate of pseudo sciences to the level of genuine sciences and technologizing them for the effective service of mankind. I call them “life-regulating,” not because they play a more important part in human affairs than do the genuine sciences of mathematics, physics, chemistry, astronomy and biology, for they are not more important than these, but because they are, so to say, closer, more immediate and more obvious in their influence and effects. These life-regulating sciences are, of course, not independent; they depend ultimately upon the genuine sciences for much of their power and ought to go to them for light and guidance; but what I mean here by saying they are not independent is that they are dependent upon each other, interpenetrating and interlocking in innumerable ways. To show in detail how the so-called sciences will have to be transformed to make them accord with the right conception of man and qualify them for their proper business will eventually require a large volume or indeed volumes. (pp. 95-97)

But of course, Korzybski was also presenting a decidedly utopian vision of human beings and society governed by the rational, scientific principles of human engineering. In doing so, he took his place as part of a tradition that dates back to Plato's

Republic, and includes Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels notorious

Communist Manifesto, Edward Bellamy's science/speculative fiction novel,

Looking Backward, and Thorsten Veblen's

The Engineers and the Price System published in the same year as

Manhood of Humanity, 1921. To be fair, Korzybski did not overtly forward a prescription for technocracy (see the interesting wikipedia article on

the technocracy movement). In the same sense that we can substitute education for engineering, Korzybski's approach emphasized individual enlightenment rather than autocratic social control, which was why it wound up having a great deal of influence over the human potential movement, and various forms of psychotherapy.

We can also discern in

Manhood of Humanity an implied theory of history, broken up into three stages of human development. The first stage could be referred to as pre-scientific, characteristic of all traditional societies, where time-binding exists, but progress is very slow. Korzybski has relatively little to say about this stage, as he was not an anthropologist or historian. Perhaps he might have referred to this as the infancy of humanity (which is not to say that I support such a characterization).

The second stage would be scientific, wherein the adoption of scientific method allows for rapid progress in specialized sectors such as applied science, technology and engineering, and in our knowledge of pure science and mathematics--but not in any other aspect of human affairs. This is what Korzybski means by the childhood of humanity.

The third stage, yet to come when Korzybski was writing this first book in 1921, and arguably still yet to come today, would be when all human life is informed by and governed by a scientific approach, human engineering as it were. I think we could refer to this period as post-scientific, not because science would be obsolete, but simply because it would become ubiquitous and environmental; this follows the same logic in which Fredric Jameson explains that the postmodern is considered the period following modernization, in which the process of modernization has been completed and is no longer an issue. This period would be the manhood of humanity, our mature phase, a stage he believed we were about to enter.

Now it's true that developmental models were all the rage in the early and mid 20th century, Toynbee's world history being a prime example, and that they have since been discredited--societies are not like organisms, evolution is not teleological, at least not from a scientific perspective. And even if we are not trying to be scientific in the sense that Korzybski advocated, I do think that our ideas have to be at the very least consistent with established scientific understandings of the world.

Be that as it may, models of historical and cultural change are not unfamiliar in other areas of the media ecology literature. For example, the pre-scientific period clearly connects to oral culture, while it is writing and especially printing that go hand in hand with the development of science. This development is especially well discussed and explained in physicist Robert K. Logan's book,

The Alphabet Effect. Writing and printing are materializations of our time-binding capacity that change the very nature of time-binding itself, applying time-binding to time-binding in self-reflexive manner, another aspect of non-Aristotelian dynamics. The technologies of writing and printing give rise to other technologies and techniques, to applied science and pure science, and to the technique of scientific method, which further improves upon our capacity for time-binding.

So, the shift from pre-scientific to scientific societies follows the shift from orality to literacy, from oral culture to literate culture. And it also follows the shift from what Neil Postman in his book

Technopoly referred to as tool-using cultures and technocratic cultures. Postman's taxonomy follows a common enough understanding about technological development, and his use of the term

technocracy refers not so much to government by engineers (although it does coincide with the advent of social science, which was often used in the service of governmental bureaucracy), but to the advent of modern science, belief in progress, and emphasis on technological development that increasingly overshadowed all else, but remained confined within its specialized sector.

So what of the post-scientific society that Korzybski looked for? We might see in Postman's dystopic vision of

technopoly, which he argued is already with us, the shadow, the dark side of Korzybski's vision, the society ruled by technology, where no sector is safe from the technological imperative, where it is all but impossible to say no to technology or imagine a value other than efficiency to invoke when deliberating and decision-making. Again this is the opposite of what Korzybski was anticipating, but they form a dialectic of sorts.

Postman's three cultures, tool-using, technocracy, and technopoly line us with the three main media environments often discussed in the media ecology literature, the oral, the literate and especially the print or typographic, and the electronic. I have discussed these correspondences elsewhere and won't go into them here.

But how interesting to consider McLuhan's vision of electronic interdependence, the global village, everyone involved in depth with each other, all in light of a post-scientific age. McLuhan wrote about a new ecological awareness that does not seem inconsistent with Korzybski's ideal of mature consciousness, nor does the related turn to relativism in the late 20th century. Yes, there seems to be a contradiction when McLuhan spoke of a return to the tribal, but on a global scale, but then again, Marx's view of a just and rational world was linked to a return to communal living, hence the term

communism. The electronic age is characterized by both irrationality and hyperrationality. And the computer, the electronic medium

par excellence, represents the triumph of a rational and mathematical approach to the world. Might it be that the computer represents the materialization of the third stage of time-binding? Just some speculation, mind you, but I do think there is an important connection between general semantics and digital technologies that has yet to be established.

Well, this post sure took a lot of time to put together, and there's still more to be said, which I'll save for next time...

Frankenstein for President!

Frankenstein for President! Vote or die!

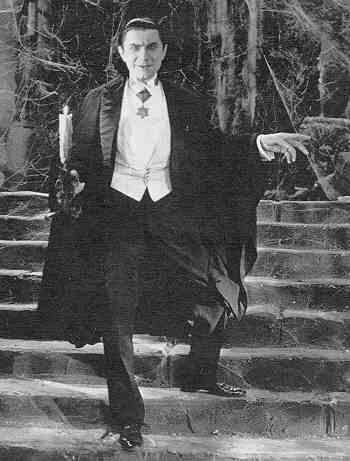

Vote or die! Dracula for President!

Dracula for President! Vote or die!

Vote or die! The Wolfman for President!

The Wolfman for President! So...

So...