So, in this centenary year of McLuhan's birth, the Guardian, arguably the leading newspaper in the United Kingdom (and one that is decidedly non-muddied or muddled by Murdoch), ran some material on our favorite media guru with which I, your humble servant, had some involvement.

It began with a podcast, one put together by Benjamen Walker, who also has a radio show over on WFMU, an independent, free form station in Jersey City, New Jersey. The podcast is part of a "Big Ideas" series, and is presented on the Guardian website as "The Big Ideas podcast: The medium is the message" followed by, "In the first of a series of philosophy podcasts, Benjamen Walker and guests discuss the communication theorist Marshall McLuhan and his most famous line," and if you can't wait to get over there and listen to it, just click here, but do come back after, and if you can wait til later, even better.

So, over on the podcast's web page, which went up last week just before McLuhan's actual birthday, the write-up goes on to say

The writing of the Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan, who would have celebrated his 100th birthday this Thursday, has entered popular jargon like that of few other modern intellectuals. Is there another line that has been quoted – and misquoted – as enthusiastically as 'the medium is the message'? McLuhan, of course, was perfectly aware of his status as the thinker du jour of the media age, the man everyone liked to quote over dinner but hadn't bothered to read – for proof, just watch Annie Hall.

But what does "the medium is the message" really mean? In the first episode of our new The Big Ideas series, Benjamen Walker gets to the bottom of the slogan with the help of Canadian novelist and McLuhan-biographer Douglas Coupland, academic Lance Strate, Marshal's son Eric McLuhan, record producer John Simon, and the Guardian's media correspondent Jemima Kiss.

So hey, I find myself in good company here, how about that? If you listen to podcast, which I think Benjamen Walker did a really great job on, very impressive Ben, but what I was saying was that if you listen to the podcast, you won't hear me you get towards the end, about the last third. But hey, I get some good play and good words in, and there's some nice discussion about McLuhan's time at Fordham University worked into the mix. Oh, and by the way, if you click on my name in the quote up above, I left the links in, it'll take you right back to this blog. How about that? Blog Time Passing is linked to on the UK Guardian website! My, how we have come up in the world!

The write-up ends with the following

Once you've finished listening to the podcast, you might want to re-read the opening of McLuhan classic essay:

The medium, or process of our time – electric technology – is reshaping and restructuring patterns of social interdependence and every aspect of our personal life. It is forcing us to reconsider and re-evaluate practically every thought, every action, and every institution formerly taken for granted. Everything is changing – you, your family, your neighbourhood, your education, your job, your government, your relation to "the others." And they're changing dramatically.

Societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by the content of the communication. The alphabet, for instance, is a technology that is absorbed by the very young child in a completely unconscious manner, by osmosis so to speak. Words and the meaning of words predispose the child to think and act automatically in certain ways. The alphabet and print technology fostered and encouraged a fragmenting process, a process of specialism and of detachment. Electric technology fosters and encourages unification and involvement. It is impossible to understand social and cultural changes without a knowledge of the workings of media.

The older training of observation has become quite irrelevant in this new time, because it is based on psychological responses and concepts conditioned by the former technology – mechanization.

Innumerable confusions and a profound feeling of despair invariably emerge in periods of great technological and cultural transitions. Our "Age of Anxiety" is, in great part, the result of trying to do today's job with yesterday's tools – with yesterday's concepts.

Youth instinctively understands the present environment – the electric drama. It lives mythically and in depth. This is the reason for the great alienation between generations. Wars, revolutions, civil uprisings are interfaces within the new environments created by electric informational media.

Marshall McLuhan, 'The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects' (1967). Reproduced with permission by Penguin BooksOver the course of the next week, we will follow up this podcast with a series of blogposts. Please tell us in the thread below what aspect of McLuhan's theory you would like us to explore, and who else you would like to hear from on the subject.

So, this was followed by a blog post by Douglas Coupland entitled, "Why McLuhan's chilling vision still matters today," and if you want to read it, just click here. I won't bother to go into it, except to say that because he got into the contemporary media environment of blogs and podcasts and Google and Facebook and Twitter, I was asked not to bring that up in the post they had me write for the Guardian website, and consequently we went back and forth through several revisions, with added editorial alterations, before it was posted yesterday. My preference was to discuss the new media, but instead they asked that I address McLuhan in the context of his times, and out of that came the emphasis on his conservatism. It wasn't the emphasis I would have chosen, but if you want to see the article on the Guardian website, click here. Or read ahead.

The Big Ideas post begins with the headline: "Marshall McLuhan's message was imbued with conservatism," followed by, "Although an icon of the counterculture movement, the man who coined 'the medium is the message' was no pill-popping hipster," neither of which were my choice, I hasten to add, nor my words exactly. I wouldn't say his message was imbued with conservatism exactly, and I wouldn't use the phrase "pill-popping hipster," not that I'm opposed to what's being said here.

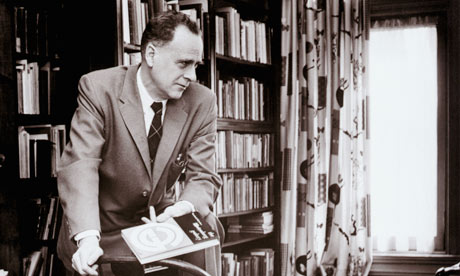

Anyway, what follows is my byline and photo, which you can see over on the left, and they actually gave me my own page of sorts, if you click on my name over on the post's page, it takes you there, or to see it direct, click here. That was very nice of them, after all, and what they say about me is, "Lance Strate is professor of communication and media studies at Fordham University in New York City. He is also an author and co-editor of The Legacy of McLuhan." Anyway, this is followed by a very nice picture of McLuhan, one I don't recall seeing before:

Anyway, what follows is my byline and photo, which you can see over on the left, and they actually gave me my own page of sorts, if you click on my name over on the post's page, it takes you there, or to see it direct, click here. That was very nice of them, after all, and what they say about me is, "Lance Strate is professor of communication and media studies at Fordham University in New York City. He is also an author and co-editor of The Legacy of McLuhan." Anyway, this is followed by a very nice picture of McLuhan, one I don't recall seeing before:And now for the article itself:

Marshall McLuhan is remembered by many for his rise to fame as the original "media guru", the subject of a multitude of newspaper and magazine articles and broadcast interviews, not to mention a cameo appearance in Woody Allen's finest film, Annie Hall.

Let me interrupt right off the bat and note that I was asked to include the Woody Allen reference at the beginning of the piece so the editor could incorporate the clip from the movie, which didn't happen, although there is a link on the site to the imdb.com page for Annie Hall. I haven't included that and the other links in this post, though.

Because McLuhan was adopted first by the counterculture movement of the 1960s and, more recently, by web evangelists, people sometimes assume that the man himself was some kind of pill-popping hipster. They couldn't be further from the truth.

Again, "pill-popping hipster," not my words, although I didn't nix them.

Far from sharing sympathy for countercultural forms of life, or the forms of media they embraced, McLuhan made a point of withholding judgment, refraining from moral evaluation of the processes he was describing and explaining. If anything, it was the conservative side of McLuhan that sometimes shone through his stance as a scientific observer. He never condemned the Vietnam war, suggesting instead that it was more of a media event than an actual happening. He discussed the possibility of using media as a form of control, "using TV in South Africa … to cool down the tribal temperature raised by radio", with no acknowledgement of the Orwellian implications.

Again, I was asked to write about this, and while it's not what I would have chosen to emphasize, it is certainly true. I've heard James W. Carey, one of McLuhan's sympathetic critics, talk about how McLuhan not coming out against the war angered him and many other academics. And the bit about South Africa was one of the most ill-considered statements he ever made, having the unfortunate effect of turning many scholars off to anything else McLuhan had to say.

As a conservative Roman Catholic, he tended to downplay the significance of the printing press in regard to the Protestant Reformation, a point stressed by many other media scholars. But the fact that his insights could be embraced by radicals and reactionaries alike is a testament to their brilliance, and to his ability to transcend his own human frailties and failings.

I haven't heard as much criticism regarding this last point, perhaps because it's more of an intramural one for media ecologists, but it is noticeable, and there has been more general accusations of a hidden agenda related to his Catholicism (which I think absurd). I just find it funny, myself, not at all offensive. And the overriding point is the fact that individuals from all different political positions, religious affiliations (and atheists), backgrounds, etc., can see the value and importance of his approach and his insights. That's what counts. From here, it's less controversial:

Even though he was later hailed as a prophet, McLuhan insisted that he was only describing what was taking place in the present, while everyone else was fixated on the past (looking "through the rear-view mirror," as he put it). Looking at electricity, electric technology and electronic media such as Samuel Morse's telegraph and Guglielmo Marconi's wireless, he was able to understand television in ways that no one else had, and to glimpse the seeds of new media environments to come. It was because he understood the present, not the future, that his insights remain as valid today as half a century ago.

McLuhan's approach is particularly well suited to helping us to understand new technologies as they are being introduced into a culture. His early rise to prominence was mainly due to his ability to explain the novel medium of television and the dramatic social upheavals that it generated. At a time when baby boomers were establishing a new, "cool" youth culture that ran counter to the "hot" outlook of their parents, McLuhan had an explanation. The "cool" cultural style was a product of the television medium, whose low-resolution image required more cognitive processing than the high-definition experience we might get from radio and the motion picture, and that processing, or participation, had a tendency to suck the audience member in, creating a great sense of involvement in the message. "Hot media", by contrast, require less cognitive effort, freeing audiences to act. This understanding led McLuhan to claim that Hitler could not have been successful in a televisual media environment.

I had just thrown in the quick reference to hot and cool in generational terms, and was asked to provide more explanation of the terms. And that's fine, but trying to squeeze it into a very short post, that is challenging. I do hope the ideas got through okay, but I know this is an oversimplification of a complex set of associations. Anyway, on to more familiar turf:

Moreover, television, in exposing viewers to the world with unprecedented immediacy and intimacy, was creating what he called a "global village", an entirely new form of tribalism that did away with private identity, individualism and the nation state – all products of print culture. The televisual window on the world was giving rise to a transparent society where we all find ourselves too close for comfort, with deep potential for aggression and violence (including, for example, terrorism).

McLuhan's famous aphorism, "the medium is the message", goes to the very heart of his way of understanding media, packing together a dozen or more different meanings. First and foremost, it is a wake-up call. McLuhan asks us to pay attention to the medium, rather than being distracted by the content. The content is not without its import, but it pales in comparison to the impact of the medium itself.

Instead of focusing solely on the content of television programming, for example, concerning ourselves with the depiction of violence, he argued that we needed to examine how the very presence of television as a medium was changing us, changing our very mode of thought from one that was characteristically linear and sequential (one thing at a time), to one that involved pattern recognition.

So, that's pretty standard Understanding Media stuff there, but this originally started with the request that I explain what "the medium is the message" is all about, so that's what I get into here at the end. And no, I didn't write, "far out" (did you think I did?).

Is all this really that far out? The bottom line is that the medium is the message because the medium has a great influence on what is communicated, on how it is used. How we go about doing a task has much to do with the way that task turns out. It is simple, commonsense stuff. We say "ask a silly question, get a silly answer" because the questions we ask determine the kinds of answers we obtain.

Supposedly more "conservative" thinkers have argued along similar lines. Henry David Thoreau observed that "we do not ride on the railroad; it rides upon us"; Mark Twain quipped that "when you have a hammer in your hand, everything looks like a nail", and Winston Churchill maintained that "we shape our buildings, and thereafter they shape us". To this last, McLuhan's colleague, John Culkin, generalised that "we shape our tools, and thereafter they shape us", by way of explaining McLuhan's perspective.

And I didn't write the bit about "more 'conservative' thinkers either, I don't really think of Thoreau or Twain as conservative, although I suppose you could say they were. I know Churchill was, of course, but I figure the Guardian being a British paper, they'd appreciate the reference. As for Culkin, he was the Jesuit who brought McLuhan to Fordham University, so probably more conservative than some, but relatively liberal I'd say. Anyway, on to my closing statement:

The medium is the message also means that the medium is the environment. Our media are extensions of ourselves, they go between ourselves and our environment, and whatever goes between us and our environment becomes our new environment. In this way, every new medium is a new environment, and affects us much as the natural environment shapes us. That is why, to understand our media environments, we need McLuhan's media ecology.

So, at least I got my bit about media ecology in at the end. And all's well that end's well, at least, that's what some Brit said. But just as an fyi, here is some of the other stuff I wrote that wound up on the cutting room floor:

McLuhan rose from relative obscurity as a Canadian academic with a doctorate from Cambridge, teaching literary criticism at schools such as Saint Louis University and the University of Toronto, and reached the peak of his celebrity in 1967, the year he came to the media capital of New York City, as Fordham University's Albert Schweitzer Professor of the Humanities, the same year that his bestselling book, The Medium is the Massage, was published. It was also the year he made the news for undergoing what had been the longest continuous brain surgery ever attempted, to remove a benign brain tumor. He returned to Toronto in 1968, where he spent the remainder of his career, until his death in 1980, eighteen months after suffering a debilitating stroke.

McLuhan's brain was as unorthodox as his thought processes, so that many found him difficult to understand, and had trouble recognizing him as one of the most important thinkers of the twentieth century. Moreover, his brilliance and originality were denied by many, some out of jealousy for his success, some out of dislike for his subject matter, some for ideological motives, some out of religious prejudice, some for personal reasons. This convergence of forces resulted in a deliberate effort to suppress his work, starting in the seventies. The cause for the current revival of interest in his work is quite clear, as it began in the nineties just as the internet became a popular phenomenon.

McLuhan's media ecology approach is particularly well suited for helping us to understand new technologies as they are being introduced into a culture, and his early rise to prominence was due to his ability to explain the new medium of television, and the dramatic social upheavals that it generated. Likewise, over the past two decades, we have experienced a deluge of innovations, including e-mail, chat, text messaging, websites, search engines, mp3s, blogs, tweets, social networking, mobile telephony, iPods and iPads, etc., and McLuhan's method is therefore especially relevant to the present day. His insights remain valid because he studied the electronic media, and while many of their characteristics were only nascent or still in potential during the sixties, they have since come into their own. For example, when he argued that television, in exposing viewers to the world with unprecedented immediacy and intimacy, was creating what he called a "global village," it was harder to relate that idea to watching I Love Lucy than it is now to the experience of internet interconnectivity, to following Facebook updates, Twitter streams, and Google search results.

And from another draft:

McLuhan's brain was as unorthodox as his thought processes, so that many found him difficult to understand, and had trouble recognizing him as one of the most important thinkers of the twentieth century. Moreover, his brilliance and originality were denied by many, some out of jealousy for his success, some out of dislike for his subject matter, some for ideological motives, some out of religious prejudice, some for personal reasons. This convergence of forces resulted in a deliberate effort to suppress his work, starting in the seventies. If his name came up at all, it was to dismiss him as a technological determinist, and throw out lines such as, "of course, the medium is not the message," evincing no effort to understand McLuhan's arguments or approach, and often enough no effort to actually read his major works, such as Understanding Media, and The Gutenberg Galaxy. It was not until the nineties, when the internet became a popular phenomenon, that there was a widespread revival of interest in his work, which continues to this day.

So, thank goodness for blogs, where I can set the record straight, sort of, and where I can find a home for these poor, wayward sentences of mine. Get along, little doggies, get along...

No comments:

Post a Comment