So, Alfred Korzybski published his magnum opus on general semantics in 1933 under the title of Science and Sanity, because he believed that scientific method gives us our best understanding of the world, our most accurate maps, as it were, of a territory that we can only really know indirectly. As a scientific approach to mental health, education, and social, political, economic, and ethical progress, general semantics caught the imagination of many science fiction writers, among them Robert Heinlein, Frank Herbert, and A. E. van Vogt. As a form of quasi-therapy, general semantics influenced a number of significant therapists, including Albert Ellis, Fritz Perls, and Albert Bandler of Neuro-Linguistic Programming fame.

Another well known figure who credited Korzybski and general semantics with having had an important impact on his thinking was L. Ron Hubbard. Understandably, many individuals associated with general semantics do not want to be associated with Hubbard, or have general semantics be connected to him in any way. And arguably, whatever Hubbard took from Korzybski he didn't use in a way that Korzybski intended or would have approved of.

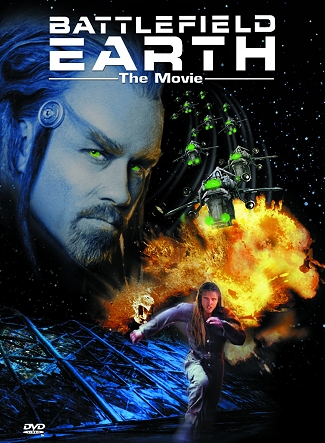

But Hubbard was, early on, a science fiction writer. I haven't read his books, I must confess, but I did see the one movie that was made based on his work. It wasn't very good, but John Travolta was quite amusing, unintentionally of course, as an alien:

Now that's what I call Saturday Night Fever!

Anyway, Hubbard eventually shifted his focus from fiction to psychotherapy (well, some say he never shifted his focus away from fiction, but that's another matter). That's when he came up with his own brand of therapy, called Dianetics. That link will take you over to the Wikipedia entry, where it says:

Be that as it may, after coming up with his Dianetics, Hubbard went on to create Scientology, and note the link here between Science and Sanity, science fiction, and Scientology as a belief system. And as you no doubt know, Hubbard established Scientology as a religion, founding the Church of Scientology in 1953. It's a religion that has been embraced by a number of celebrities, and quoting now from the Wikipedia entry on the Church, here's the section on celebrities:

Now I don't know about you, but I was a bit surprised when, while watching the Superbowl a few weeks ago, this commercial popped up:

According to a piece by Cavan Sieczkowski in the Huffington Post entitled Church Of Scientology Super Bowl Ad Raises Eyebrows, the Church did not actually buy a Superbowl ad, the most expensive of all possible commercial placements. A small portion of advertising time is reserved for the local and regional stations running the Superbowl network feed, and the Church bought time on the stations in a few major markets, including New York and Los Angeles, a much cheaper proposition, but one that gave the impression that they were willing and able to afford the highest advertising rates in the universe. Sieczkowski goes on to relate the following:

And this brings me to the point that got me onto this topic in the first place. In a story over on gawker.com, with a headline of The Atlantic Is Now Publishing Bizarre, Blatant Scientology Propaganda as ‘Sponsored Content’, Taylor Berman wrote

And here, Berman provides a quote from the sponsored article in The Atlantic:

Berman goes on to note that the article focues "on Miscavige's plans to expand the religion's already existing churches" and adds another quote from The Atlantic:

Well, it is not surprising that The Atlantic removed the piece, given this sort of scathing criticism. Berman's critique ends with the following update:

In a story that appeared in Business Insider, Jim Edwards explains

Another well known figure who credited Korzybski and general semantics with having had an important impact on his thinking was L. Ron Hubbard. Understandably, many individuals associated with general semantics do not want to be associated with Hubbard, or have general semantics be connected to him in any way. And arguably, whatever Hubbard took from Korzybski he didn't use in a way that Korzybski intended or would have approved of.

But Hubbard was, early on, a science fiction writer. I haven't read his books, I must confess, but I did see the one movie that was made based on his work. It wasn't very good, but John Travolta was quite amusing, unintentionally of course, as an alien:

Now that's what I call Saturday Night Fever!

Anyway, Hubbard eventually shifted his focus from fiction to psychotherapy (well, some say he never shifted his focus away from fiction, but that's another matter). That's when he came up with his own brand of therapy, called Dianetics. That link will take you over to the Wikipedia entry, where it says:

When Hubbard formulated Dianetics, he described it as "a mix of Western technology and Oriental philosophy". He said that Dianetics "forms a bridge between" cybernetics and General Semantics (a set of ideas about education originated by Alfred Korzybski, which received much attention in the science fiction world in the 1940s)—a claim denied by scholars of General Semantics, including S. I. Hayakawa, who expressed strong criticism of Dianetics as early as 1951.

Be that as it may, after coming up with his Dianetics, Hubbard went on to create Scientology, and note the link here between Science and Sanity, science fiction, and Scientology as a belief system. And as you no doubt know, Hubbard established Scientology as a religion, founding the Church of Scientology in 1953. It's a religion that has been embraced by a number of celebrities, and quoting now from the Wikipedia entry on the Church, here's the section on celebrities:

Hubbard envisaged that celebrities would have a key role to play in the dissemination of Scientology, and in 1955 launched Project Celebrity, creating a list of 63 famous people that he asked his followers to target for conversion to Scientology. Former silent-screen star Gloria Swanson and jazz pianist Dave Brubeck were among the earliest celebrities attracted to Hubbard's teachings.

Today, Scientology operates eight churches that are designated Celebrity Centers, the largest of these being the one in Hollywood. Celebrity Centers are open to the general public, but are primarily designed to minister to celebrity Scientologists. Entertainers such as John Travolta, Kirstie Alley, Lisa Marie Presley, Nancy Cartwright, Jason Lee, Isaac Hayes, Edgar Winter, Tom Cruise, Chick Corea and Leah Remini have generated considerable publicity for Scientology.

Now I don't know about you, but I was a bit surprised when, while watching the Superbowl a few weeks ago, this commercial popped up:

According to a piece by Cavan Sieczkowski in the Huffington Post entitled Church Of Scientology Super Bowl Ad Raises Eyebrows, the Church did not actually buy a Superbowl ad, the most expensive of all possible commercial placements. A small portion of advertising time is reserved for the local and regional stations running the Superbowl network feed, and the Church bought time on the stations in a few major markets, including New York and Los Angeles, a much cheaper proposition, but one that gave the impression that they were willing and able to afford the highest advertising rates in the universe. Sieczkowski goes on to relate the following:

This is the second time in recent weeks a Scientology ad has broken into the mainstream media.

In mid-January, the Atlantic published promotional, sponsored content by the Church of Scientology detailing how the church's “ecclesiastical leader,” David Miscavige, had led it to its best year yet. The advertorial package was denounced by readers, and the Atlantic promptly removed the post after receiving a wave of backlash.

And this brings me to the point that got me onto this topic in the first place. In a story over on gawker.com, with a headline of The Atlantic Is Now Publishing Bizarre, Blatant Scientology Propaganda as ‘Sponsored Content’, Taylor Berman wrote

The Atlantic –- the one time publisher of Mark Twain, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edith Wharton –- is now publishing Scientology propaganda. The "sponsored content", bought and paid for by the Church of Scientology, went up Monday around noon and features all sorts of breathless praise for Scientology and its alleged growth last year.

The post—an example of the kind of advertising many publishers are turning to as display ad revenue stagnates—is basically one long tribute to David Miscavige, the "ecclesiastical leader of the Scientology religion":

And here, Berman provides a quote from the sponsored article in The Atlantic:

Mr. Miscavige is unrelenting in his work for millions of parishioners and the cities served by Scientology Churches. He has led a renaissance for the religion itself, while driving worldwide programs to serve communities through Church-sponsored social and humanitarian initiatives.

Berman goes on to note that the article focues "on Miscavige's plans to expand the religion's already existing churches" and adds another quote from The Atlantic:

David Miscavige spearheaded a program to build every Church of Scientology into what Scientology Founder L. Ron Hubbard termed "Ideal Organizations" (Ideal Orgs). This new breed of Church is ideal in location, design, quality of religious services and social betterment programs. Each is uniquely configured to accommodate the full array of Scientology services for both parishioners and the surrounding community. Ideal Orgs further house extensive public information multimedia displays that introduce every facet of Dianetics and Scientology, along with libraries, course and seminar rooms for an introduction to and study of Scientology Scripture. Chapels serve to host Sunday Services and other congregational gatherings.And Berman then adds

It is from these Ideal Churches that Scientologists extend their humanitarian programs to mitigate intolerance, illiteracy, immorality and drug abuse.

The post then lists the "unprecedented 12 Ideal Scientology Churches" built around the world last year, including locations in Germany, California, Italy and Israel, with accompanying pictures of each opening's celebration.

And let's not forget the comments. Of the 17 comments posted as of this writing, 11 are so pro-Scientology they read as though they're an extension of the original post. A bold, proud day for The Atlantic and its fine history of journalistic excellence.

Well, it is not surprising that The Atlantic removed the piece, given this sort of scathing criticism. Berman's critique ends with the following update:

The Atlantic took down the post, writing: "We have temporarily suspended this advertising campaign pending a review of our policies that govern sponsor content and subsequent comment threads."

In a story that appeared in Business Insider, Jim Edwards explains

A lot of magazines sell sponsored content to advertisers. (Business Insider has several sponsored content series running right now, for instance.) The usual rule is that such stories must be clearly labeled so that readers can see whether editorial may have been influenced by advertisers. Normally, however, both the publisher and the advertiser try to make the content credible or useful in some way, because readers can spot blatant propaganda a mile away -- and that's of no use to anyone.So now for the good part. A journalist by the name of Mike Daly writes for an online news site by the name of Adotas, described as where interactive advertising begins, and Mike's bio goes like this:

Blatant propaganda, however, is exactly what The Atlantic appears to have published. The article, titled "David Miscavige Leads Scientology to Milestone Year," was an encomium to the the "ecclesiastical" leader of the church and his many accomplishments (which mostly include buying old buildings and turning them into new churches, according to the article).

The Atlantic is a highbrow magazine known for it famous writers and agenda-shaping journalism. This, decidedly, was not it.

Mike Daly is an award-winning writer and editor with nearly 30 years of experience in publishing. He began his career in 1983 at The News of Paterson, N.J., a long-since defunct daily paper, where at age 22 he was promoted to the position of Editorial Page Editor. Since then he has served in managerial capacities with several news organizations, including Arts Weekly Inc. and North Jersey Media Group in New Jersey and Examiner Media in New York. His work has been honored on numerous occasions by the New Jersey Press Association and the Society for Professional Journalists.So he's the real deal. And Daly does a feature on Adotas called Today's Burning Question, and on January 18th the burning question was, "What can be learned from The Atlantic’s Scientology Sponsored Story debacle?" He then collects answers from industry contacts, which in this case includes

- Ari Brandt, CEO of MediaBrix

- Dave Martin, SVP, Media at Ignited

- Ari Jacoby, CEO of Solve Media

- Richard Spalding, CEO, The 7th Chamber

- Laney Whitcanack, EVP of Conversational Marketing at Federated Media Publishing

- David E. Johnson, CEO, Strategic Vision, LLC

- and me

And if you want to read all of the replies, especially of these other folks, by all means, go check it out over at Adotas, under the heading of Today’s Burning Question: The Atlantic’s Sponsored Scientology Story Debacle. But for my quote alone, well, you know it's gotta make an appearance here on Blog Time Passing:

“The Atlantic’s embarrassed retraction of sponsored content serves as a reminder that the established ways of doing business for traditional media industries are no longer working. When print media dominated, it was easy to specialize and compartmentalize content and operations, leading to the journalistic ideal of strict separation between advertising and news, and more generally between financial considerations and editorial judgment, often invoked metaphorically as “church and state”. The public relations industry sought to scale the walls by providing ready-made content for news media, for example in the form of press releases, but this content was typically offered free of charge and taken up by news media free of charge. For this reason, public relations professionals were previously viewed with great suspicion by journalists and advertisers alike, but today emerge as having superior ethics overall than many news and advertising professionals. As electronic media came to dominate the culture, beginning with broadcasting, but more fully with the Internet, we’ve seen the boundaries between different types of content blurring in many different areas, such as docudrama, edutainment, infomercials, advertorials, and product placement in motion pictures and television programming. And online, the boundaries grow even fuzzier, as it is often not clear whether the source of a particular blog or YouTube video is a private individual, organization, or business. Digital technologies have presented new challenges to advertising that have led to efforts to break out of the compartment of a labeled advertisement, as it becomes easier and easier for audiences to ignore that type of content, while the same technologies have severely undermined the business model of periodicals such as The Atlantic, so both of these traditional media industries are struggling financially, and sponsored content must seem like a marriage made in heaven. What they failed to take into account is that in the electronic media environment, there are intrinsic values that differ from those of the print media environment. Print media favored content, facts, logical structure and organization. Electronic media favor transparency, honesty, self-disclosure, and a sense of genuineness in the presentation of real personality and appearance. Much of what is valued in the electronic media environment was missing in the way that The Atlantic presented Scientology’s sponsored content, and so the content and the sources were immediately rejected and ridiculed by audiences, and this can have a negative effect on the reputations of the magazine, and possibly the sponsor as well.” — Dr. Lance Strate, Professor of Communication and Media Studies and Director of the Professional Studies in New Media program at Fordham University.

Now, that is rather long winded, I must admit, and it is the longest of the responses. How it stacks up to the others I leave up to you to judge. One thing is certain, however, and that is that the science of sponsored content has a long way to go yet before it reaches a state of sanity, and that the new media environment is very unforgiving of maps that mislead us about the territory they are supposed to represent.